Chien de guerre - Définition

La liste des auteurs de cet article est disponible ici.

Images

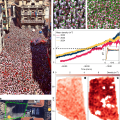

U.S. Army working dog wearing body armor clears a building in Afghanistan. |

Post WWII cartoon emphasizing the importance of canines in medical research. | ||

| Ambulance dogs search for wounded men through scent and hearing. |

Usages

Chien anti-char

Durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, l'Union soviétique entraina des chiens à détruire des tanks. Ces chiens étaient d'abord entrainés pour trouver de la nourriture sous les tanks. Ils étaient ensuite affamés avant d'être utilisés. Lâchés non loin des tanks ennemis et de poches contenant des explosifs, les chiens se dirigeaient sous les chars croyant y trouver de la nourriture. Les explosifs étaient déclenchés par un dispositif de mise à feu qui s'allumait lorsque le dos du chien se pliait pour passer sous le tank, sacrifiant l'animal

Il fut rapporté que onze véhicules blindés allemands furent détruits au cours d'une seule bataille Ils furent considérés comme suffisamment dangereux pour que les Panzergrenadiers allemands se firent ordonner de tuer à vue tout chien. Cependant, les chiens ne pouvaient distinguer les chars allemands des chars soviétiques et étaient aussi facilement effrayés par les combats et par les chars en déplacement, malgré leur faim. Le projet fut par la suite abandonné par les Soviétiques.

Chiens de combat

Dans l'Antiquité, des chiens, souvent des races de type mastiff, étaient revêtus d'une armure et de collier clouté et envoyés à la bataille pour attaquer l'ennemi. Cette utilisation a été utilisée par différentes civilisations comme les Romains ou les Grecs. Cet emploi a été largement abandonné dans la période moderne de l'histoire militaire, les armes modernes pouvant tuer les chiens presqu'immédiatement. comme lors de la bataille d'Okinawa où des soldats américains éliminèrent un escadron de soldats japonais et leurs chiens.

Logistique et transmissions

Au moment du déclenchement de la Première Guerre mondiale, plusieurs armées européennes utilisaient les chiens pour tirer de petits chariots Beaucoup d'armées européennes adaptèrent le procédé à des fins militaires.. L'armée de terre belge utilisait des chiens pour tirer leur mitrailleuses et d'autres fournitures ou blessés dans des carrioles. Les Français possédaient 250 chiens au début de la Première Guerre mondiale. Les Néerlandais copièrent l'idée et eurent des centaines de chiens entrainés et prêts à la fin du conflit (les Pays-Bas restèrent neutres durant cette guerre). Les Soviétiques utilisèrent également des chiens pour tirer les blessés vers les postes de secours durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Les chiens étaient bien adaptés pour transporter des charges sur des terrains enneigés ou couverts de cratères de bombes.

Les chiens étaient souvent utilisés pour transmettre des messages durant la bataille. Ils pouvaient être renvoyés de manière silencieuse vers un second maitre. Cela nécessitait d'avoir un chien qui soit loyal à deux maitres différents, sinon le chien risquait de ne pas délivrer le message à temps voire pas du tout.

Mascottes

Les chiens étaient souvent utilisés comme mascotte d'unités militaire. Le chien pouvait être le chien d'un officier, un chien que l'unité adoptait ou l'un des chiens utilisés comme chien de travail . Certains unités choisirent d'utiliser toujours la même race de chien comme mascotte. Cette présence d'une mascotte était conçue pour augmenter le moral des troupes, et nombreuses furent utilisées dans ce but dans les tranchées durant la Première Guerre mondiale.

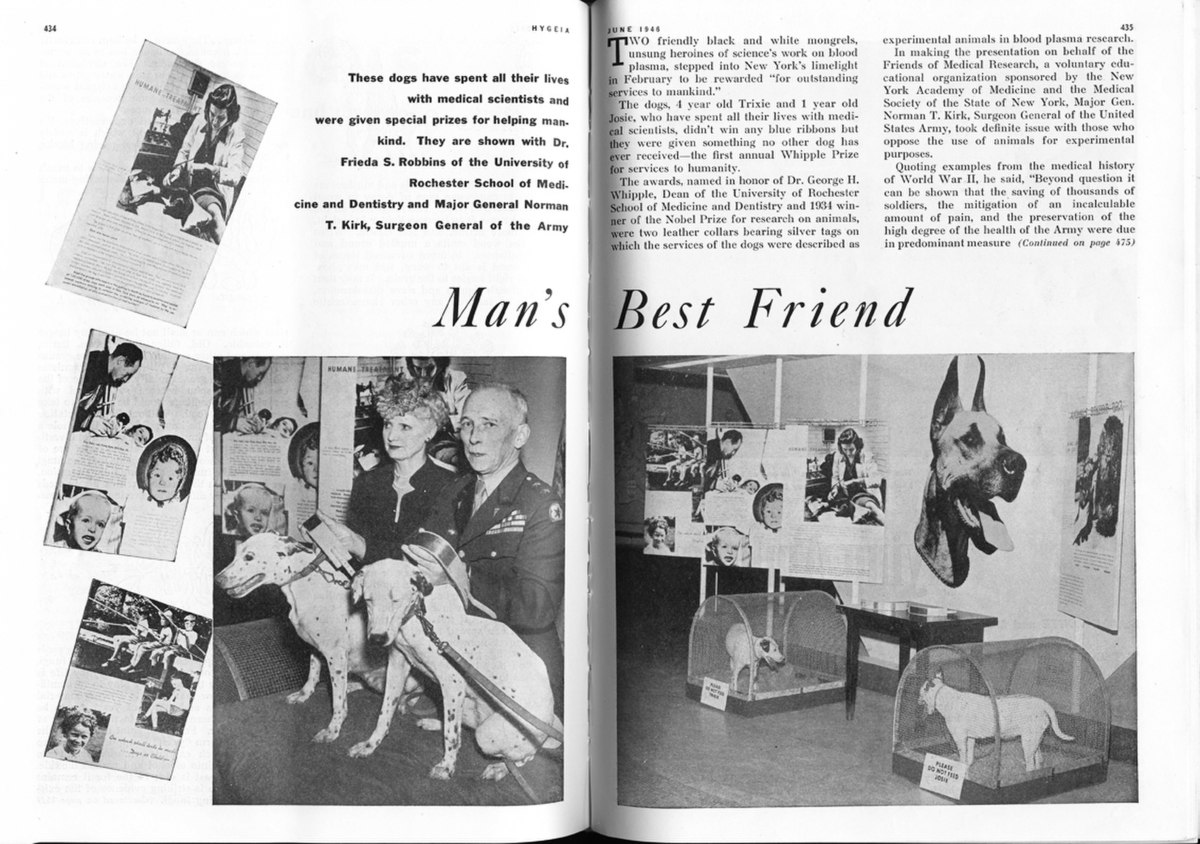

Recherche médicale

Lors de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, les chiens prirent un nouveau rôle dans l'expérimentation animale, devenant les principaux animaux pour la recherche médicale L'expérimentation animale permettait aux médecins de tester de nouveaux traitements sans risque sur l'homme, mais cette pratique fut regarder plus attentivement après la guerre. Le gouvernement américain répondit en disant que ces chiens étaient des héros.

La guerre froide souleva un débat animé sur l'éthique de l'expérimentation animale aux États-Unis, particulièrement sur la manière dont des chiens avaient été traités durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale En 1966, des réformes majeures intervinrent avec l'adoption du Laboratory Animal Welfare Act, loi sur le bien-être des animaux de laboratoire.

Détection et pistage

De nombreux chiens furent utilisés pour localiser des mines. Ils ne se révélèrent pas très efficace en conditions de combat. Marine mine detecting dogs were trained using bare electric wires beneath the ground surface. The wires shocked the dogs, teaching them that danger lurked under the dirt. Once the dog's focus was properly directed, dummy mines were planted and the dogs were trained to signal their presence. While the dogs effectively found the mines, the task proved so stressful for the dogs they were only able to work between 20 and 30 minutes at a time. The mine detecting war dogs anticipated random shocks from the heretofore friendly earth, making them extremely nervous. The useful service life of the dogs was not long. Experiments with lab rats show that this trend can be very extreme, in some tests rats even huddled in the corner to the point of starvation to avoid electric shock.

Dogs have historically also been used in many cases to track fugitives and enemy troops, overlapping partly into the duties of a scout dog, but use their olfactory skill in tracking a scent, rather than warning a handler at the initial presentation of a scent.

Scouts

Some dogs are trained to silently locate booby traps and concealed enemies such as snipers. The dog's keen senses of smell and hearing would make them far more effective at detecting these dangers than humans. The best scout dogs are described as having a disposition intermediate to docile tracking dogs and aggressive attack dogs.

Scout dogs were used in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam by the United States to detect ambushes, weapon caches, or enemy fighters hiding underwater, with only reed breathing straws showing above the waterline. The US operated a number of scout dog platoons (assigned on a handler-and-dog team basis to individual patrols) and had a dedicated dog training school in Fort Benning, Georgia.

Sentinelles

One of the earliest military-related uses, sentry dogs were used to defend camps or other priority areas at night and sometimes during the day. They would bark or growl to alert guards of a stranger's presence. During the Cold War, the American military used sentry dog teams outside of nuclear weapons storage areas. A test program was conducted in Vietnam to test sentry dogs, launched two days after a successful Vietcong attack on Da Nang Air Base (July 1, 1965). Forty dog teams were deployed to Vietnam for a four month test period, with teams were placed on the perimeter in front of machine gun towers/bunkers. The detection of intruders resulted in a rapid deployment of reinforcements. The test was successful, so the handlers returned to the US while the dogs were reassigned to new handlers. The Air Force immediately started to ship dog teams to all the bases in Vietnam and Thailand.

The buildup of American forces in Vietnam created large dog sections at USAF Southeast Asia (SEA) bases. 467 dogs were eventually assigned to Bien Hoa, Bien Thuy, Cam Ranh Bay, Da Nang, Nha Trang, Tuy Hoa, Phu Cat, Phan Rang, Tan Son Nhut, and Pleiku Air Bases. Within a year of deployment, attacks on several bases had been stopped when the enemy forces were detected by dog teams. Captured Vietcong told of the fear and respect that they had for the dogs. The Vietcong even placed a bounty on lives of handlers and dogs. The success of sentry dogs was determined by the lack of successful penetrations of bases in Vietnam and Thailand. It is estimated by the United States War Dogs Association that war dogs saved over 10,000 U.S. lives in Vietnam. Sentry Dogs were also used by the Army, Navy, and Marines to protect the perimeter of large bases.

Usages modernes

Contemporary dogs in military roles are also often referred to as police dogs, or in the United States as a Military Working Dog (MWD), or K-9. Their roles are nearly as varied as their ancient cousins, though they tend to be more rarely used in front-line formations.

Traditionally, the most common breed for these police-type operations has been the German Shepherd; in recent years there has been a shift to smaller dogs with keener senses of smell for detection work, and more resilient breeds such as the Belgian Malinois and Dutch Shepherd for patrolling and law enforcement. All MWDs in use today are paired with a single individual after their training. This person is called a handler. While a handler usually won't stay with one dog for the length of either's career, usually a handler will stay partnered with a dog for at least a year, and sometimes much longer.

In the 1970s the US Air Force used over 1600 dogs worldwide. Today, personnel cutbacks have reduced USAF dog teams to approximately 530, stationed throughout the world. Many dogs that operate in these roles are trained at the Lackland Air Force Base, the only United States facility that currently trains dogs for military use.

Change has also come in legislature for the benefit of the canines. Prior to 2000, older war dogs were required to be euthanized. Thanks to a new law, retired military dogs may now be adopted, the first of which was Lex, a working dog whose handler was killed in Iraq.

There are numerous memorials dedicated to war dogs, including at March Field Air Museum in Riverside, California, at The Infantry School, Ft. Benning, Georgia; at the Naval Facility, Guam, with replicas at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine in Knoxville and the Alfred M. Gray Marine Corps Research Center in Quantico, Virginia.

Police

As a partner in everyday military police work, dogs have proved versatile and loyal officers. Police dogs can chase suspects, track them if they are hidden, and guard them when they are caught. They are trained to respond viciously if their handler is attacked, and otherwise not to react at all unless they are commanded to do so by their handler. Many police dogs are also trained in detection as well.

Détection de drogue et d'explosif

Both MWDs and their civilian counterparts provide service in drug detection, sniffing out a broad range of psychoactive substances despite efforts at concealment. Provided they have been trained to detect it, MWDs can smell small traces of nearly any substance, even if it is in a sealed container. Dogs trained in drug detection are normally used at ports of embarkation such as airports, checkpoints, and other places where there is high security and a need for anti-contraband measures.

MWDs can also be trained to detect explosives. As with narcotics, trained MWDs can detect minuscule amounts of a wide range of explosives, making them useful for searching entry points, patrolling within secure installations, and at checkpoints. These dogs are capable of achieving over a 98% success rate in bomb detection.

Intimidation

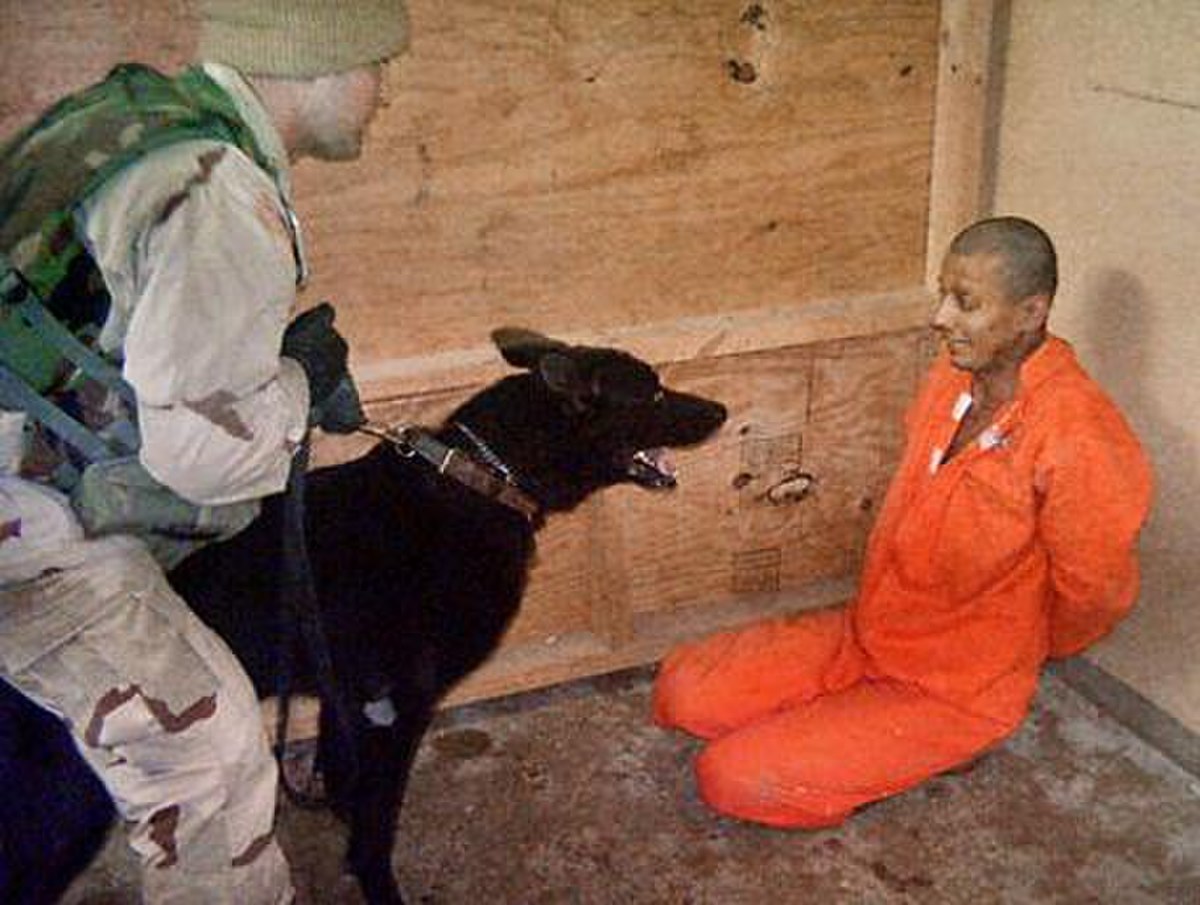

The use of Military Working Dogs on prisoners by the United States during recent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq has been very controversial.

War in Iraq: The U.S. has used dogs to intimidate prisoners in Iraqi prisons. In court testimony following the revelations of Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse, it was stated that Col. Thomas M. Pappas approved the use of dogs for interrogations. Pvt. Ivan L. Frederick testified that interrogators were authorized to use dogs and that a civilian contract interrogator left him lists of the cells he wanted dog handlers to visit. "They were allowed to use them to ... intimidate inmates", Frederick stated. Two soldiers, Sgt. Santos A. Cardona and Sgt. Michael J. Smith, were then charged with maltreatment of detainees, for allegedly encouraging and permitting unmuzzled working dogs to threaten and attack them. Prosecutors have focused on an incident caught in published photographs, when the two men allegedly cornered a naked detainee and allowed the dogs to bite him on each thigh as he cowered in fear.

Guantanamo Bay: It is believed that the use of dogs on prisoners in Iraq was learned from practices at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. The use of dogs on prisoners by regular U.S. forces in Guantanamo Bay Naval Base was prohibited by Donald Rumsfeld in April 2003. A few months later following revelations of abuses at Abu Ghraib prison, including use of dogs to terrify naked prisoners; Rumsfeld then issued a further order prohibiting their use by the regular U.S. forces in Iraq.

Autres rôles

Military Working dogs continue to serve as sentries, trackers, Search and rescue, scouts, and mascots. Retired working dogs are often adopted as pets or Therapy dogs.