Why are there four seasons, and not three or five?

Published by Redbran,

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

We learn about them from a very young age. Then, we listen to poets and musicians striving to brighten up the coldness of winter, rejoice at the return of spring, delight in the arrival of summer, and melancholically celebrate the fallen leaves of autumn.

But have you ever wondered why there are four seasons?

Measuring time, at the intersection of astronomy and the arbitrary

The terms we use to measure the passage of time are numerous and varied in origin. Sometimes, these choices are arbitrary: we decided to divide the day into 24 hours; we could have chosen differently. We called a period of seven days a "week" following the creation of the world in the biblical tradition. However, in France, the republican calendar, implemented on September 21, 1792, and abolished by Napoleon in 1806, had a 10-day week: primidi, duodi, tridi, quartidi, quintidi, sextidi, septidi, octidi, nonidi, and décadi!

But sometimes, the choices have an objective foundation, particularly astronomical: thus, the year corresponds to the duration of the Earth's revolution around the Sun, and the month is linked to the duration of the Moon's revolution around the Earth.

What about the seasons? Why four?

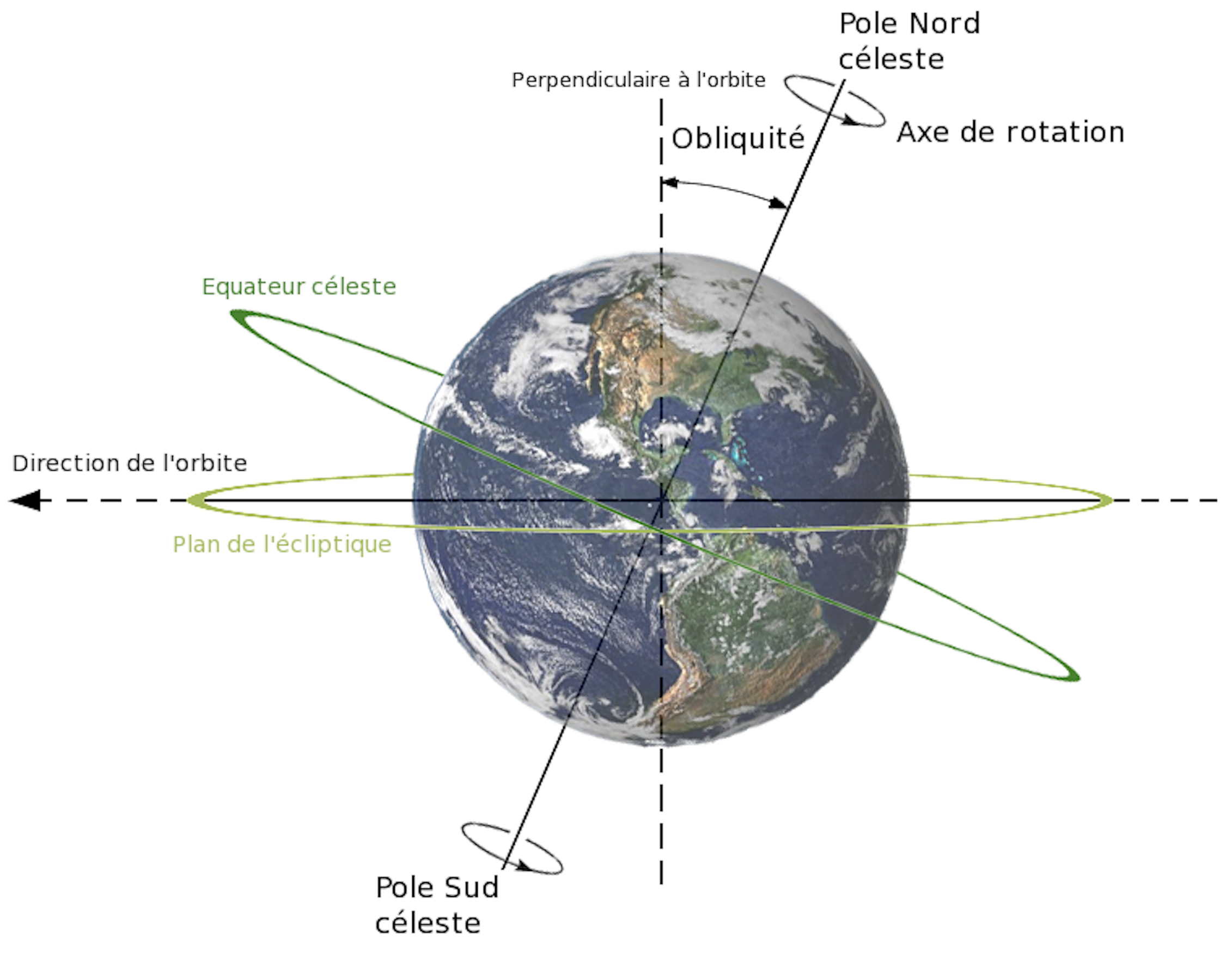

The modern understanding of this number is essentially astronomical. Let's examine this. The Earth has a dual movement: a flat trajectory around the Sun, called the ecliptic, and a rotation on its own around the south-north axis. This axis, whose direction can be considered fixed as the Earth moves along its orbit, is tilted by approximately 23 degrees from the perpendicular to the plane of the ecliptic. Therefore, the Earth rotates around the sun with the poles' axis inclined relative to the ecliptic.

Description of Earth's axial tilt (obliquity) and its relationship to the planes of the ecliptic, the celestial equator, and the axis of rotation. Earth is shown as viewed from the Sun and its orbit is counter-clockwise (thus moving to the left).

AxialTiltObliquity.png, CC BY

Solstices and equinoxes as markers of seasonal change

As a result, seen from a specific point on Earth, the apparent trajectory of the Sun in the sky changes throughout the year. The Sun always rises in the east and sets in the west, but it climbs higher in the sky in summer than in winter. Consequently, the length of the day increases as we approach summer and decreases as we approach winter.

The longest day of the year is called the summer solstice, which occurs on June 21, and the shortest day is the winter solstice, which occurs on December 21 (there may be a day's difference due to leap years).

Between these two extremes, there are naturally two days when the duration of night is equal to that of the day: these are the equinoxes (from the Latin aequus, equal, and nox, night). The spring equinox occurs when the length of the day is increasing (March 21 or 22, depending on the year), and the autumn equinox occurs when the length is decreasing (September 22 or 23, depending on the year). It is also the day when the Sun passes directly over the equator. The seasons are divided among these four specific moments of the year, hence... the number of seasons, quite simply!

Agriculture, another powerful marker of time passage

We should now go back in time and note that this astronomical explanation has not always prevailed - as one might suspect. But phenomena do not depend on the knowledge we have of them (!), and their effects on agricultural practices have been observed in every civilization and have even served religious practices.

For instance, in ancient Egypt, the flooding of the Nile was crucial for crops, so the year was divided into three seasons of four months each: akhet, the flooding period, peret, the water recession, and chemu, the hot harvest season. In Assyria in the early 2nd millennium, there were also three seasons (spring, summer, winter) defined by the agricultural tasks to be carried out.

It is also amusing to note that the first mention of December 25 as the birthday of Jesus dates back to 336 AD, coinciding with the traditional celebration of Sol invictus (the Unconquered Sun), marking the beginning of the lengthening of daylight.

Taking agriculture as a marker of time might seem distant today, but we still retain this link in the etymology of the word season, which comes from the Latin sationem, a noun meaning "sowing action". More anecdotally, the importance of agriculture in measuring time is evident through the many proverbs associated with the day's saint, providing guidance on harvests, sowing, and crops. For instance, "On St. Catherine's day, all wood takes root" indicates that November 25 is a significant date for planting trees.

In the era of climate change: new seasons?

However, in recent decades, harvests have been disrupted by the reality of climate change, due to disturbances in the water cycle. Indeed, an increase in the average global temperature of 1°C (1.8°F) results in a 7% increase in the atmosphere's water vapor content. We also expect temperate zones to become more arid, arid zones more desert-like, and some tropical areas uninhabitable.

Thus, some media have been tempted to name, for example, "super summer" or "Indian summer" these unusually hot and dry autumns, and even wonder if we should now talk about five seasons or if winter has simply disappeared.

However, it is unlikely that this will change the naming of the seasons: it is too ingrained in our culture, as evidenced by the universally known work of Vivaldi, the musician, and the equally famous work of the painter Arcimboldo!