How does neuroscience explain consciousness?

Published by Adrien,

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

Consciousness is one of the most complicated and complex notions. Complicated because it is difficult to understand, and complex because it encompasses several intertwined elements, making it hard to grasp. Let's take a brief tour of three "rival" theories currently defended by scientists.

Several theories stand in opposition among scientists in the attempt to unravel the mysteries of our inner lives.

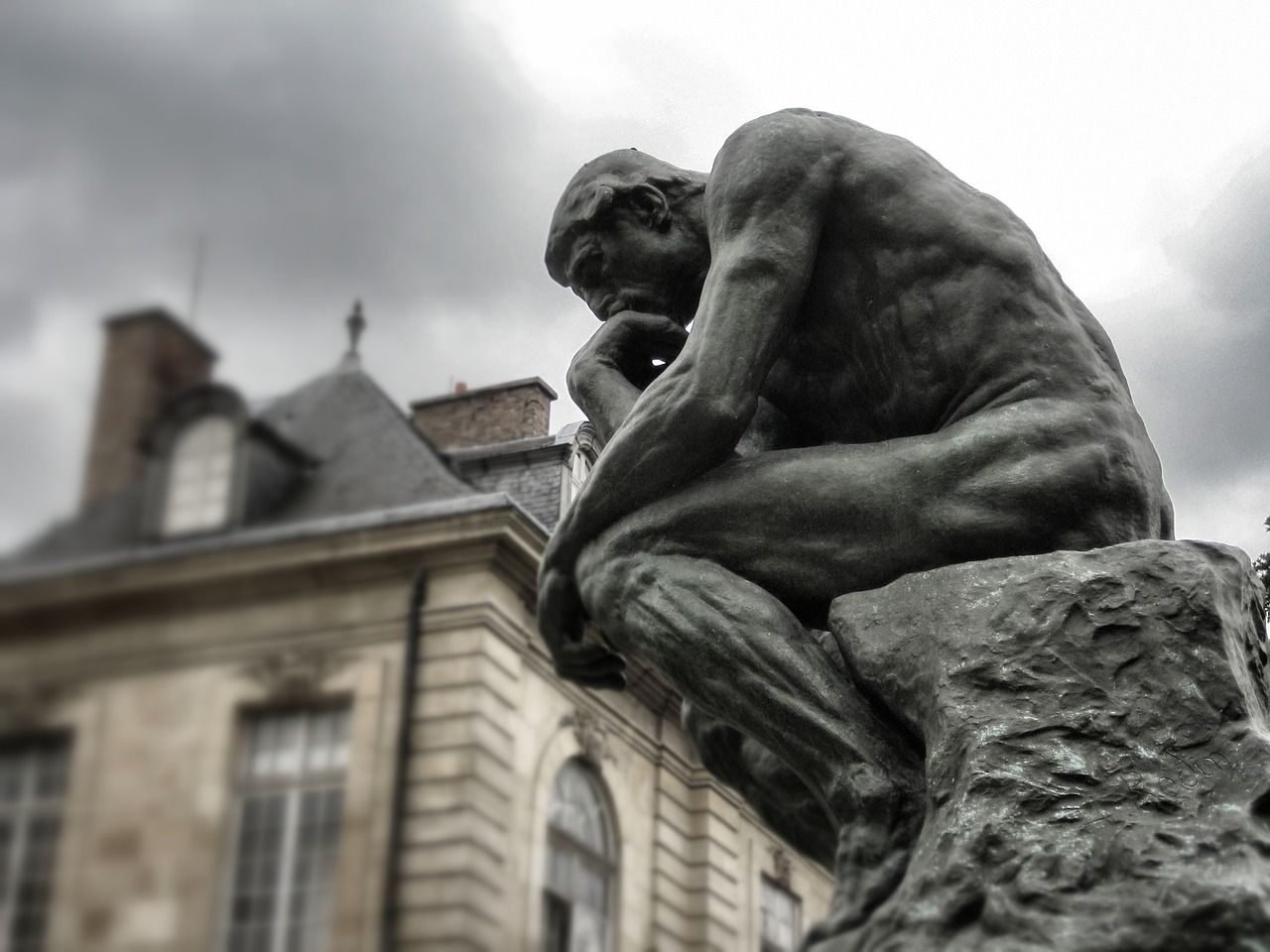

Avery Evans/Unsplash

According to the Larousse dictionary, consciousness is the "immediate intuitive or reflective awareness each person has of their existence and the external world." It is important to distinguish several types of consciousness.

Spontaneous or immediate consciousness is related to experience and oriented towards the external world. It refers to the individual's presence to themselves at the moment they think, feel, or act. Reflective consciousness is the ability to reflect on one's own thoughts or actions and analyze them. Lastly, the term "conscience" can also refer to our moral judgment, involving the notions of right and wrong, a sense that does not pertain to what interests us here.

Are we on the verge of discovering the signature of consciousness?

Advancements in neuroscience, computing, and engineering since the 1950s suggest the possibility of decoding the mind and even, according to some, one day "uploading" it onto a digital medium. Yet, consciousness still eludes scientists. Indeed, the illumination of increasingly precise and specific brain mechanisms opens a new relationship with the brain and reopens the question: will we discover the neuronal signature of consciousness? In this quest to identify the brain mechanisms underlying this complex phenomenon, science needs theories.

In this debate, which initially was philosophical, scientific theories of consciousness take a materialistic approach. This means they hypothesize that consciousness is a phenomenon emerging from the matter we are made of, as opposed to dualists who believe body and mind are two different natures. Scientists then rely on the analysis of brain activity.

The Global Workspace Theory

The Global Workspace Theory is a functional theory: it seeks to describe consciousness through what it does and the functions it fulfills. It explains that becoming conscious emerges from the interaction between several brain regions and processes that unite. The aim is also to adopt an experimental approach without necessarily promoting a "divine project" to justify the existence of consciousness. It was formulated in the late 1980s by the American neuroscientist Bernard Baars, and supported by French neuroscientists Stanislas Dehaene, Lionel Naccache, and Jean-Pierre Changeux.

The main idea of this theory is that when we receive sensory information, it is first rapidly processed automatically by specialized brain regions, such as the visual cortex. It has been observed that if this information is not maintained and amplified by a broader neural network, it remains unconscious. Becoming conscious is a slower but more flexible process than automatic processes, bringing together information from different specialized networks.

Some sensory information is thus selected to be spread across many brain regions, like the prefrontal cortex. These brain regions are highly connected to many other brain regions. This convergence process towards a single coherent interpretation of the situation brings forth a unique state of consciousness. Once we are aware of seeing or hearing something, it is possible to perform a wide variety of mental operations. This state of consciousness manifests as a "flare-up" of brain activity, occurring 300 milliseconds after perception.

The Integrated Information Theory

Integrated Information Theory is also a functional theory, stating that consciousness is defined not by the brain's structure or activity but by a system's (organic in the case of the brain) ability to perceive a large amount of information. According to this theory, a conscious system generates information that is confronted with itself: this is called integration.

This theory, proposed by the American Giulio Tononi in 2004, postulates two fundamentals: abundant information and integration of this information. This would result in constructing a unique and irreducible mental state. Rather than starting from brain activity to explain consciousness, Tononi seeks to define a theoretical framework explaining, according to him, why certain systems like the brain, which is an organ, are conscious and experience things in a subjective way that seems independent of matter.

According to Tononi, this theory sets a framework opening other hypotheses on how to proceed so that other systems, for example, artificial ones, may become conscious. Thus, organoids and embryoids cultivated in laboratories or even plants could be considered conscious. However, this theory lacks detail: it postulates two essential elements without explaining why consciousness emerges and what characterizes it. It continues to be developed, albeit highly controversial, and was labeled "unfalsifiable pseudoscience" in a letter written by 124 experts in the field. In this publication, neuroscientists expose their differing opinions.

Higher-order Theories

Emerging from philosophy and defended by philosopher David Rosenthal and psychologist Michael Graziano, higher-order theories aim to explain the distinction between conscious and unconscious information processing. These theories postulate that consciousness consists of perceptions or thoughts about immediately accessible mental states, termed "first-order," like raw sensations. Awareness of a stimulus's content is possible only when a "higher-order" representation or "meta-representation" appears. According to these theories, there are therefore conscious thoughts based on an unconscious level of sensations, and it is the perceptions at another level of these sensations that access consciousness.

The existence of this higher-order representation makes us aware of the contents they target: perception is an automatic process, and it becomes conscious when this representation becomes a conscious thought. For British neuroscientist Edmund Rolls, it is a mechanism that allows error correction and action planning. Finally, according to these theories, unconscious processing would suffice for task execution, not necessarily requiring consciousness.

What are the stakes in the current context?

Human consciousness reveals that we exist as unique human beings, a blend of our emotions, thoughts, experiences, personality, and biology. Today, it is an unresolved philosophical and scientific question driving debates. The question of consciousness is one of meaning: who am I? What is interiority? Scientists are not yet done with this challenge, although it is not impossible we may one day explain what consciousness is.

Another area under exploration by scientists, brain organoids, also sheds light on these questions. Appearing in 2008 to compensate for the lack of knowledge on the brain's embryonic development, these "mini-brains" in Petri dishes are neuronal structures derived from stem cells. The evolution of protocols to reproduce different parts of the brain necessary for consciousness now allows for the creation of a sophisticated network of neurons capable of generating brain waves. Organoids could become sensitive and conscious artificial systems. These research efforts highlight the important question that ties all these theories: what structure is indispensable for consciousness? How does it arise and from what? Can self-awareness exist without a body? Brain organoids also raise very important ethical questions.

Today's theoretical research on consciousness takes place within a context of fervor surrounding neurotechnologies. Brain-machine interface projects like Neuralink are increasingly numerous, aiming to allow us to act on the world simply with our minds. Therefore, we must ensure that this new knowledge on consciousness, far from being confined to theoretical models, is used for the common good, without compromising our mental integrity, privacy, security, and freedom of thought.