How did our brain evolve?

Published by Redbran,

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

The unique nature and exceptional capabilities of the human brain continually amaze us. Its rounded shape, complex organization, and long maturation set it apart from the brains of other current primates, especially the great apes to whom we are directly related.

What are these specificities due to? Since the brain does not fossilize, we must seek answers by examining the skull bones found at paleontological sites to trace back through history. The cranial cavity holds imprints of the brain that provide valuable data on the 7 million years of brain evolution separating us from our oldest known ancestor: Toumaï (Sahelanthropus tchadensis).

During growth, the brain and its container, the skull, maintain a close relationship, and through a process of modeling and remodeling, the bone records the position of the grooves on the brain's surface, delineating the lobes and cerebral areas. Paleo-neurologists use these imprints to reconstruct the evolutionary history of our brain (e.g., when and how human brain specificities appeared) and to form hypotheses about the cognitive abilities of our ancestors (e.g., when they began making tools).

South Africa has played a central role in researching and discovering clues about the major stages of our brain's evolution. The paleontological sites in the "Cradle of Humankind", listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, are particularly rich in fossils trapped in ancient caves whose deposits are now exposed on the surface.

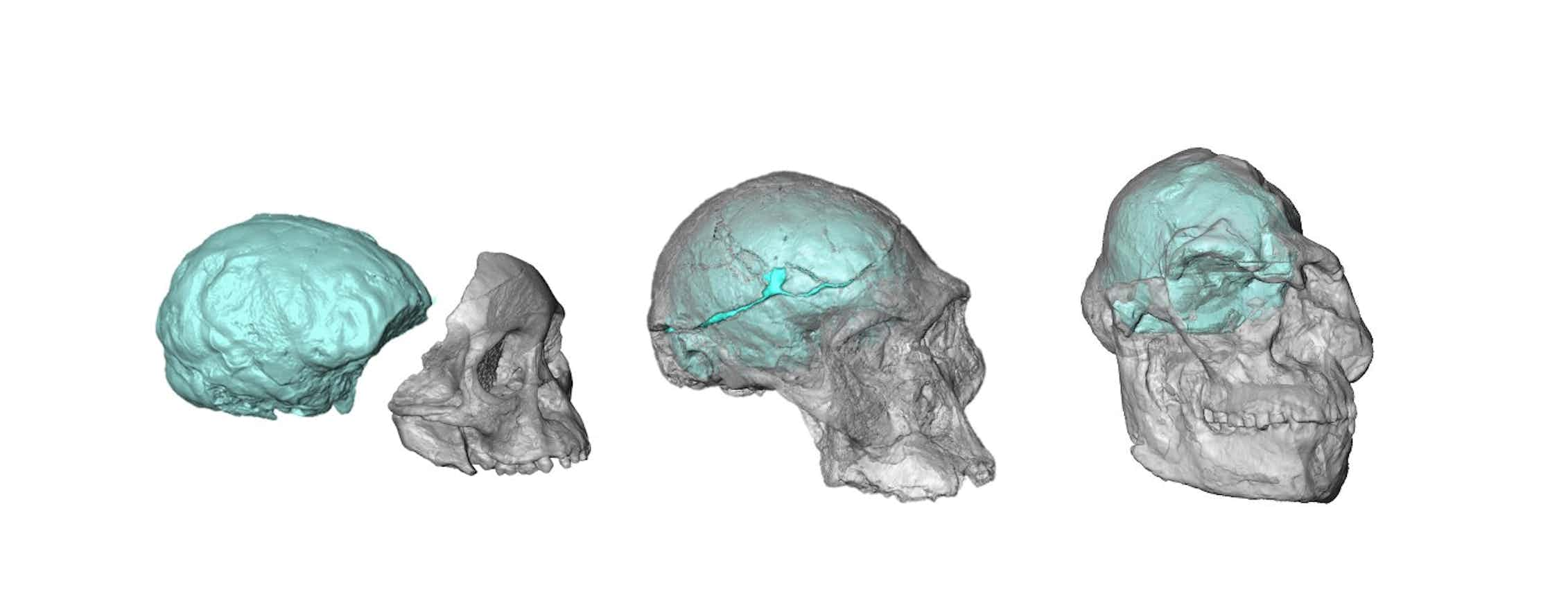

Reconstruction of the brain of the "Taung Child" (left), "Mrs. Ples" (center), and "Little Foot" (right). The bone and the external surface of the brain are respectively represented in gray and blue.

Amélie Beaudet, Provided by the author

Among these fossils are iconic specimens like the "Taung Child" (3-2.6 million years ago), the first fossil of the human lineage discovered on the African continent, which led to the recognition of the genus Australopithecus, or "Little Foot" (3.7 million years ago), the most complete skeleton of an Australopithecus ever found (50% more complete than "Lucy" discovered in Ethiopia and dated to 3.2 million years).

These exceptional sites have also led to the discovery of relatively complete skulls (e.g., "Mrs. Ples," dated to 3.5-3.4 million years) as well as natural internal casts of skulls (e.g., the "Taung Child") that preserve traces of the brains of these fossilized individuals, studied by experts and used as references for decades.

Technology in the service of paleo-neurology

Despite the relative abundance and remarkable preservation of South African fossil specimens compared to contemporary East African sites, studying the brain imprints they preserve is limited by the difficulty in deciphering and interpreting these traces.

Given this challenge, our team of paleontologists and neuroscientists first sought to integrate technical skills in imaging and computing into the study of fossil specimens.

We then established the EndoMap project, developed around a collaboration between French and South African research teams, to further explore the brain by incorporating virtual visualization and analysis methods.

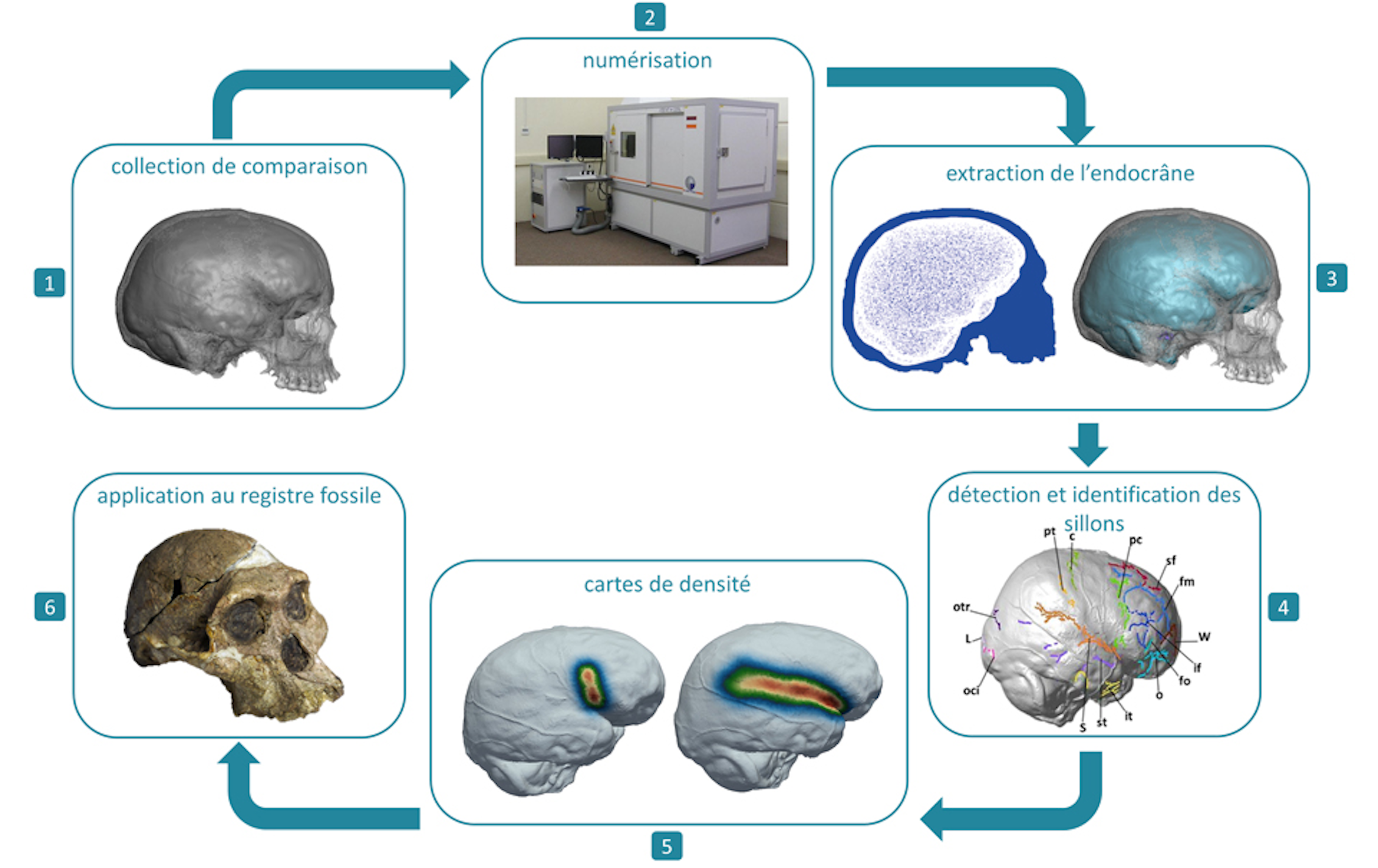

Summary of the approach developed by the EndoMap project.

EndoMap, Provided by the author

Using 3D digital models of fossil specimens from the "Cradle of Humankind" and a digital reference of extant primate skulls, we developed and provided a unique database of maps to identify principal differences and similarities between the brains of our ancestors and our own.

These maps are based on the traditional atlas approach used in neuroscience and facilitated both a better understanding of the variability in the spatial distribution of grooves in the current human brain and the identification of brain characteristics in fossils. Indeed, some major scientific disagreements in this field are due to our lack of knowledge about inter-individual variation, leading to over-interpretation of differences between fossil specimens.

Envisioning the future of paleo-neurology

However, EndoMap faces a major challenge in the study of fossil remains: how to analyze incomplete specimens or those where some brain imprints are missing or illegible? This problem of missing data, well-known in computing and common to many scientific disciplines, hampers progress in our research on brain evolution.

The recent technological leap in artificial intelligence allows glimpsing a solution. Specifically, given the limited number of fossil specimens and their unique nature, methods of artificial sample augmentation can offset the reduced sample size problem in paleontology. Additionally, the use of deep learning with more complete current samples presents a promising path for developing models capable of estimating the missing parts of incomplete specimens.

In 2023, we invited to Johannesburg paleontologists, geoarchaeologists, neuroscientists, and computer scientists from the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town (South Africa), the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom), the University of Toulouse, the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, and the University of Poitiers to contribute to our thinking on the future of our discipline at the symposium "BrAIn Evolution: Palaeosciences, Neuroscience and Artificial Intelligence" co-organized with IFAS-Research.

This discussion led to the special issue of the IFAS-Research journal, Lesedi, which has just been published online and summarizes the results of these interdisciplinary exchanges. Following this meeting, the project received financial support from the CNRS Mission for Cross-disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Initiatives (MITI) within the framework of the call for projects "Digital Twins: New Frontiers and Future Developments" to integrate AI into paleo-neurology.