Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

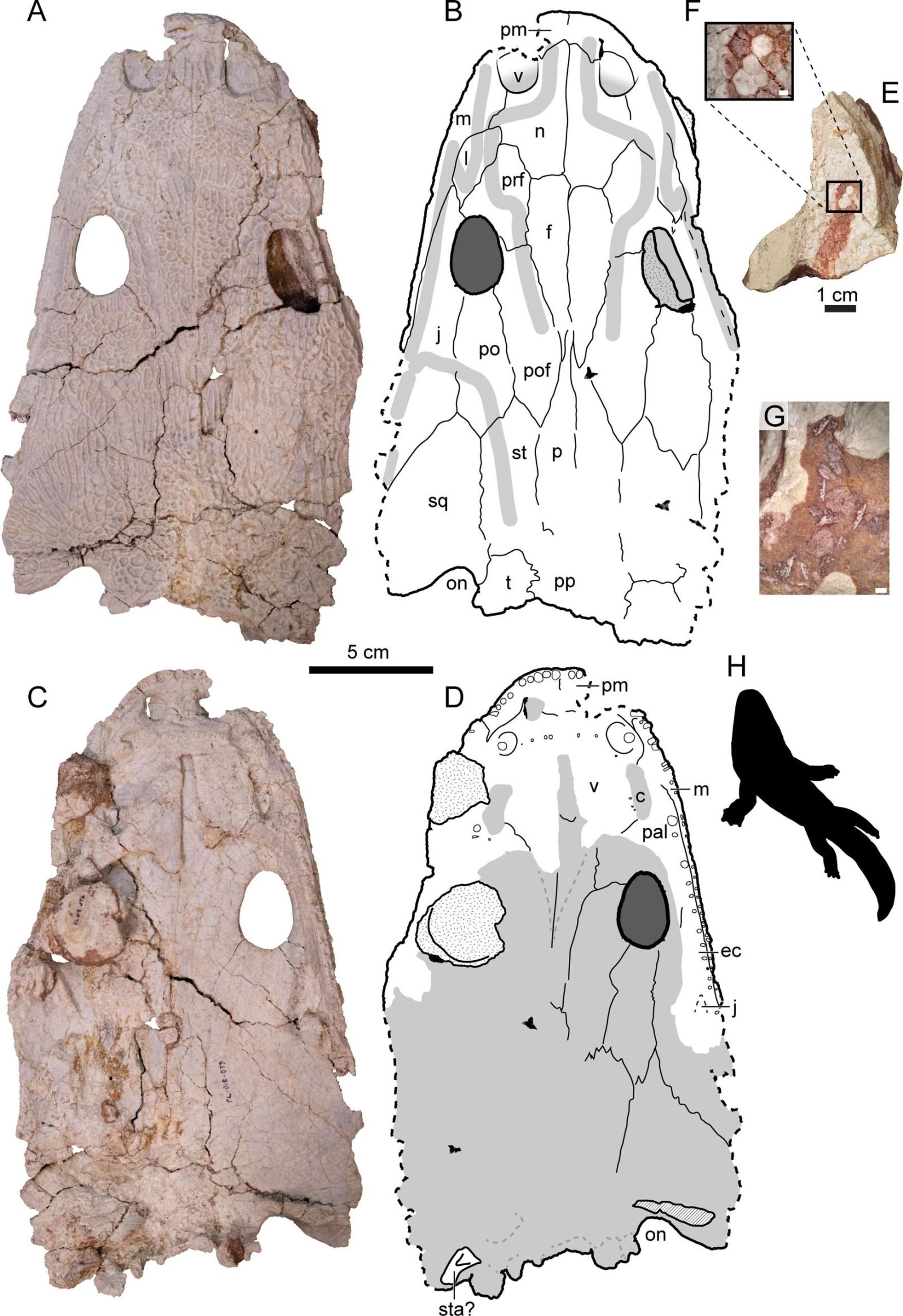

Skull of Buettnererpeton bakeri discovered in Wyoming.

Credit: Dave Lovelace, CC-BY 4.0

Researchers have studied an exceptional fossil site at Nobby Knob in Wyoming. They found dozens of giant amphibians, temnospondyls, that died together approximately 230 million years ago. The fine sediments suggest a floodplain environment where calm conditions allowed for excellent skeleton preservation.

Analysis reveals these animals were not transported by currents after death. Their arrangement and preservation state indicate they died on the spot. Scientists are considering two scenarios: a breeding colony or a drought-induced concentration.

This fossil accumulation represents over half of known Buettnererpeton bakeri specimens. It provides a unique opportunity to study this species and its environment. Researchers emphasize the importance of such discoveries for understanding Upper Triassic ecosystems.

The study published in PLOS One sheds light on the formation conditions of this deposit. Unlike other similar sites, the absence of currents allowed exceptional preservation. The authors call for more research to understand the frequency of such events.

Buettnererpeton bakeri specimens from the Nobby Knob site.

Credit: Kufner et al., 2025, PLOS One, CC-BY 4.0

Temnospondyls were dominant predators in Triassic aquatic environments. Their massive disappearance at Nobby Knob raises questions about their ecological niche. Scientists hope other sites will undergo similarly detailed analyses.

This discovery doubles the number of known Buettnererpeton bakeri specimens. It provides a rare snapshot of an entire population frozen in time. Researchers highlight the importance of systematic excavation methods for such studies.

What is a temnospondyl?

Temnospondyls were a diverse group of prehistoric amphibians that dominated aquatic ecosystems for over 200 million years. They ranged in size from a few centimeters to several meters long (from inches to several yards) and occupied various habitats from swamps to rivers.

Their unique anatomy, with broad flat skulls, made them effective predators. Temnospondyls survived several mass extinctions before disappearing in the early Cretaceous. Their study helps scientists understand the evolution of modern amphibians.

Temnospondyl fossils are often found in groups, suggesting social behavior or mass mortality events. The Nobby Knob site is a remarkable example, providing clues about their lifestyle and ecology.

How are fossil deposits formed?

Fossil deposits result from specific conditions that favor organism preservation after death. Rapid burial under sediments is essential to protect remains from decomposition and predators.

Calm aquatic environments like lakes or floodplains are often conducive to fossilization. The absence of currents allows fine sedimentation that preserves skeletal details. The Nobby Knob site is a perfect example.

Studying fossil deposits requires a multidisciplinary approach combining geology, paleontology and taphonomy. These investigations reveal not only the causes of organism death but also the environmental conditions of their time.