Covid-19: in hindsight, which countries responded best during the pandemic? 😷

Published by Adrien,

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Source: The Conversation under Creative Commons license

Other Languages: FR, DE, ES, PT

Follow us on Google News (click on ☆)

A recent study compares the different strategies implemented to combat the Covid-19 pandemic in 13 Western European countries and the results they achieved. Its findings indicate, among other things, that countries that restricted social contacts early on managed to save more lives than others, while also better preserving their economies.

Illustration image Unsplash

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the strategies implemented to contain the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, which causes the disease, varied from one country to another, even among countries with similarities in terms of population, living standards, healthcare systems, governance models, seasonality of respiratory diseases, etc.

In September 2023, representatives from 13 Western European countries involved in managing the Covid-19 pandemic (including the author of this article) chose to compare the strategies used in each country to counter the pandemic. Five years after the start of the pandemic, here is what these findings, published in the journal BMC Global and Public Health, teach us.

Choosing a relevant indicator

For this study, it was decided that the main indicator for evaluating the strategies used would be the excess mortality from all causes during the period from January 27, 2020, to July 3, 2022.

Certainly, the impact of the pandemic on our societies extends far beyond just the mortality associated with the virus. For example, we can cite the morbidity due to long Covid, the deterioration of the population's mental health caused by the pandemic, its effects on education, the economy, etc. Each of these aspects would deserve a separate analysis.

However, this indicator has many advantages for assessing the relevance of the strategies implemented. It allows:

- the use of data available in all countries by sex, age group, and week (except for Ireland, where data were available by month);

- to avoid the debate: death "from" Covid-19 or death "with" Covid-19;

- not to worry about the completeness of Covid-19 testing among deceased individuals, which could have varied between countries;

- to account for delayed mortality related to the aftereffects of Covid-19, such as cardiovascular damage;

- to include indirect mortality related to the disruption of the healthcare system during the pandemic;

- to account for the decrease in mortality due to the absence of flu epidemics for two years, and the reduction of some other causes of mortality (such as road accidents during lockdown);

- to use methods already developed to calculate excess mortality during seasonal flu epidemics or flu pandemics.

We limited our study to the period between January 2020 and July 2022, as the occurrence of a heatwave during the summer of that year, followed by the return of the flu during the winter of 2022-2023, made it impossible to attribute the observed excess mortality solely to the effects of Covid-19.

Finally, compared to most previously published articles, we made two methodological changes: we extended the reference period used to calculate the trend from which excess mortality would be estimated (2010-2019 instead of 2015-2019) and we standardized excess mortality by age and sex to account for differences in the age distribution of the populations in the selected countries, which can be very significant.

Italy, for example, has the highest proportion of people over 80 in Europe (it was 7.5% in 2020), while in Ireland it was half that (3.5%). However, we know that the oldest segments of the population were particularly vulnerable to the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus.

Early measures are more effective

Over the entire study period, from January 27, 2020, to July 3, 2022, it appears that the Scandinavian countries (Norway, Denmark, and Sweden) and Ireland fared the best: cumulative excess mortality was 0.5 to 1 per 1,000 inhabitants. The next three countries are Germany, Switzerland, and France, with cumulative excess mortality between 1.4 and 1.5. Then come Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Belgium (between 1.7 and 2.0). Finally, Italy brings up the rear, with cumulative excess mortality of 2.7.

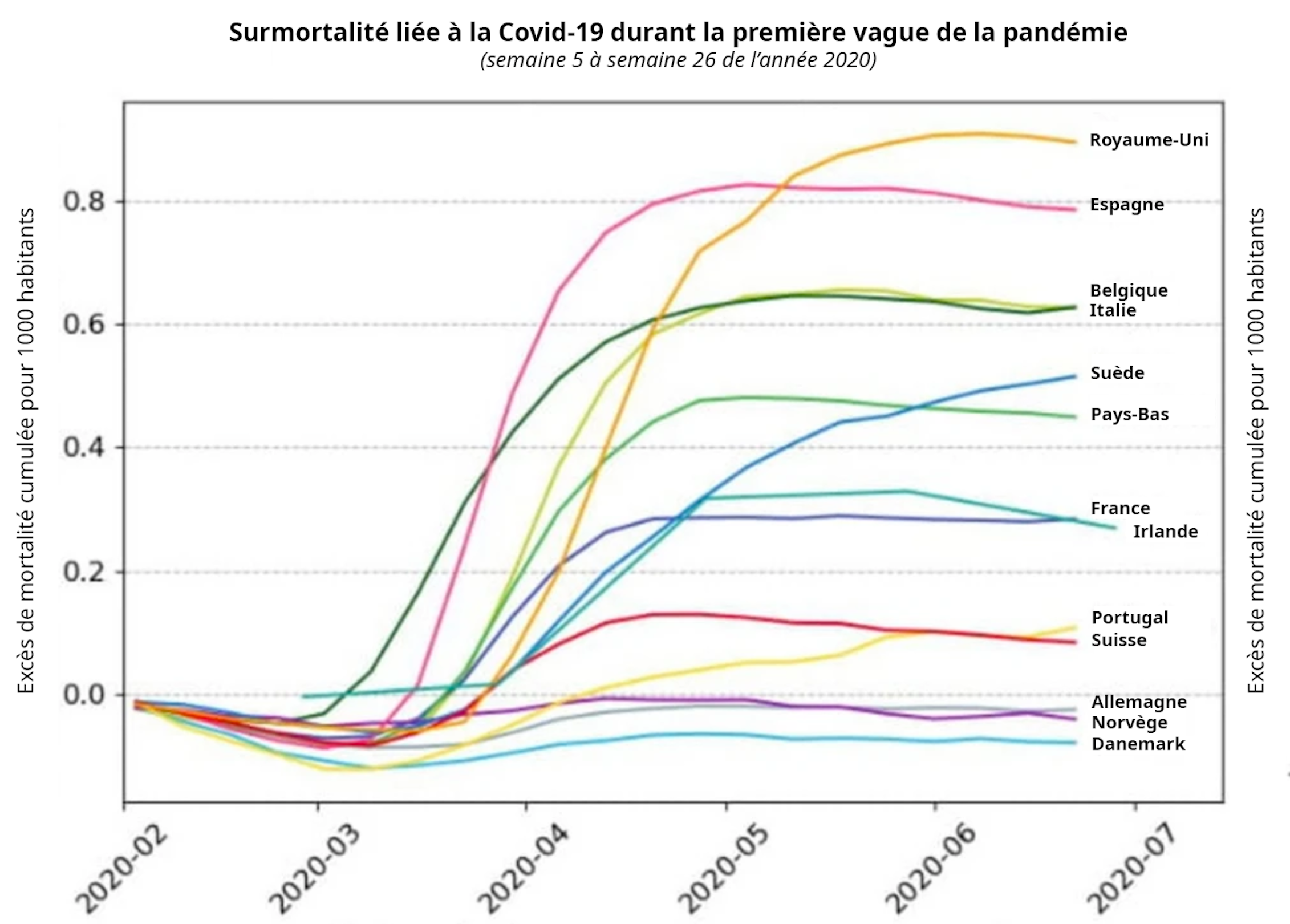

The most interesting period is probably that of the first wave (which lasted from the end of January to the end of June 2020), as it provides lessons on the strategy to follow if a new large-scale pandemic were to occur.

Cumulative excess mortality standardized by age and sex in 13 Western European countries, from January 27, 2020, to June 28, 2020 (historical strain of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus).

Adapted from Galmiche S., et al. (2024) "Patterns and drivers of excess mortality during the Covid-19 pandemic in 13 Western European countries", BMC Global and Public Health, CC BY-SA

To judge the timeliness of social contact restriction measures (lockdowns, curfews, closures...), we looked at the weekly hospitalization rate of Covid-19 patients at the time these measures were implemented. The lower this rate, the earlier we considered the measures to have been taken.

We found that excess mortality during this period was lowest in countries that implemented measures the earliest. It was even negative for countries like Germany, Denmark, and Norway, due to a shortened flu epidemic.

France, which locked down when only three regions were affected (Grand Est, Île-de-France, and Hauts-de-France), did not fare too badly. Indeed, the lockdown allowed "freezing" the emerging epidemic in the west and south of the country.

The countries with the highest excess mortality during the first wave were Spain and the United Kingdom. Both were hit by widespread epidemics across their territories from the outset, and the UK was the last Western European country to implement strong epidemic control measures (on March 24, 2020).

Sweden: an initial choice that was not successful

Sweden is the only country that initially chose intermediate measures, based on recommendations appealing to the civic-mindedness of its citizens (encouraged to voluntarily isolate if symptomatic, prioritize remote work, and limit social interactions), without implementing a lockdown or closing schools, bars, restaurants, or businesses. Only the elderly, due to their vulnerability to severe forms of the disease, were explicitly asked to isolate.

This strategy was driven by the fear of "pandemic fatigue" in the population if measures were to last, and by the expected secondary benefit of building population immunity if the virus circulated quietly among the younger population.

In hindsight, it appears that excess mortality was very high in Sweden during the first period, incomparable to its Scandinavian neighbors, and 80% higher than in France. This is explained by the fact that the virus eventually found its way into Swedish nursing homes, where mortality was very high.

The authorities acknowledged in late 2020 the failure of their strategy and advocated for stronger measures for the winter of 2020-2021. Sweden would subsequently experience a trajectory similar to that of other Scandinavian countries.

Early measures better preserved the economy

The second lesson from our study is that countries that implemented measures early not only better preserved human lives but also better preserved their economies. The drop in GDP in 2020 was indeed less significant in these countries than in those that delayed their response. And this, even though one of the reasons cited by some leaders of the latter for delaying the implementation of restrictive measures was precisely the preservation of the economy.

This can be partly explained by the fact that countries that took early measures were able to ease these measures sooner, due to a controlled health situation. Thus, Denmark, which reacted as early as March 13, 2020, when there were only ten people hospitalized in the country, was able to ease restrictions as early as April 15 (in France, it was not until May 11).

The lesson is clear: once it is known that an epidemic wave is coming and that it will be severe, there is no reason to wait for hospitals to fill up before implementing necessary restrictive measures. On the contrary, they should be put in place as early as possible. This way, lives will be saved, and the impact on the economy will be less.

Trust in institutions, key to success

Another benefit associated with early measures is that they can be calibrated. When a first set of measures is taken early, it is possible to assess their impact on the dynamics of the epidemic.

In the case of respiratory viruses like the flu virus or coronaviruses, if the measures taken have an effect, it will be noticeable within ten days on hospital admissions. If, after this period, these do not decrease, it means that the measures are insufficient and need to be strengthened.

This margin of maneuver does not exist if one waits for hospitals to be saturated before taking restrictive measures. In such a case, there is no choice but to adopt very strong measures from the outset to try to protect hospitals.

However, it should be emphasized that for a population to accept the implementation of restrictive measures even when hospitals are still empty, its trust in its government and institutions must be high. This is the third lesson from this study: the countries that were able to take early measures are those where the levels of trust in the population were the highest.

Unfortunately, the intense circulation of "fake news" and the massive impact of disinformation on public debate and decision-making do not inspire optimism in the event that we have to face a new pandemic. Let us hope that we will nevertheless remember the lessons learned, sometimes harshly, during the Covid-19 pandemic.